This week we look at the oft-cited third most common form of the primary dementias, that of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and we discuss some of the causes and some common symptoms. There are a number of names used for dementia with Lewy Bodies, and it can be abbreviated as (DLB. For this blog we use DLB as that is the common cross over abbreviation most used in the UK and the US.

However, to quickly recap as we always do when discussing the biology of dementia: every person living with a dementia is unique. Dementia itself is not an illness or any one specific disease process, rather it is a syndrome, a term used to describe a collection of related diseases and pathologies.

A syndrome is a collection of signs and symptoms that can be commonly grouped together and are recognised as producing a similar outcome even if the causes may be different.

There are well over 140 different types of ‘dementia’ and it is probable more will come to light in the next decade, however we have agreed that the general public commonly believe that when any reference to ‘dementia’ is made we are referring to someone living with Alzheimer’s disease, but as you will read again this week, often, we are not.

Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a form of dementia that shares characteristics with both Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.

DLB is a disease associated with abnormal deposits of a protein called alpha-synuclein in the brain. These deposits, called Lewy bodies, affect chemicals in the brain whose changes, in turn, can lead to problems with thinking, movement, behavior, and mood.

DLB is one of the most common causes of dementia, after Alzheimer’s disease and vascular disease.

It is a type of dementia with many complex care needs and has a sometimes remitting presentation but characteristically has some similarities with Parkinson’s disease and this includes movement disorders.

Early DLB symptoms are often confused with similar symptoms found in diseases like Alzheimer’s. Also, DLB can occur alone or along with Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease.

There are two types of DLB – dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia. The earliest signs of these two diseases differ but reflect the same biological changes in the brain. Over time, people living with a dementia with Lewy bodies or Parkinson’s disease dementia may develop very similar symptoms.

There are a number of psychiatric presentations associated with DLB, particularly hallucinations and these can prove extremely distressing to both the person and their families. These symptoms can be difficult to treat effectively due to the high sensitivity reported with this particular form of dementia to many of the medications normally associated with treatment.

Types of Lewy body dementia include:

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) – one of the more common forms of progressive dementia. Symptoms such as difficulty sleeping, loss of smell and visual hallucinations often precede movement and other problems by as long as 10 years, which consequently results in DLB going unrecognised or misdiagnosed as a psychiatric disorder until its later stages.

Neurons in the substantia nigra that produce dopamine die or become impaired and the brain’s outer layer (cortex) degenerates. Many of the neurons that remain will also contain Lewy bodies.

Later in the course of DLB, some signs and symptoms are similar to DAT and may include memory loss, poor judgment, and confusion.

Other signs and symptoms of DLB are similar to those of Parkinson’s disease, including difficulty with movement and posture, a shuffling walk, and changes in alertness and attention.

Given these similarities, DLB can be very difficult to diagnose. There is no cure for DLB, but there are medications that can control some of the symptoms. The medications used to control DLB symptoms can make motor function worse or exacerbate hallucinations, and the medications needed to treat psychiatric outcomes can be extremely dangerous to people living with DLB

Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) – a clinical diagnosis related to DLB that can occur in people with Parkinson’s disease. PDD may affect memory, social judgment, language, or reasoning.

Autopsy studies show that people with PDD often have amyloid plaques and tau tangles similar to those found in people with DAT, though it is not understood what these similarities mean.

A majority of people with Parkinson’s disease develop dementia, but the time from the onset of movement symptoms to the onset of dementia symptoms varies greatly from person to person.

Risk factors for developing PDD include the onset of Parkinson’s-related movement symptoms followed by mild cognitive impairment and REM sleep behaviour disorder, which involves having frequent vivid nightmares and visual hallucinations.

Dementia with Lewy bodies is sometimes referred to by other names, including Lewy body dementia, Lewy body variant of Alzheimer’s disease, diffuse Lewy body disease, cortical Lewy body disease and senile dementia of Lewy body type. All these terms refer to the same disorder.

DLB appears to affect men and women equally, although unusually it appears to affect slightly more men than women.

DLB accounts for up to 20 percent of people with dementia worldwide. DLB typically begins at age 50 or older, however as with all forms of dementia, it is more prevalent in people over the age of 65.

Like most dementias it is also a progressive disease, meaning symptoms start slowly and worsen over time. The disease lasts an average of 5 to 7 years from the time of diagnosis to death, but the time span can range from 2 to 20 years.

Clinical features

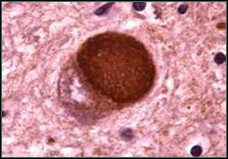

Lewy bodies are named after Dr. Friederich Lewy, a German neurologist. In 1912, he discovered abnormal protein deposits that disrupt the brain’s normal functioning in people with Parkinson’s disease. These abnormal deposits are now called ‘Lewy bodies’.

Lewy bodies are made of a protein called alpha-synuclein. In the healthy brain, a protein associated with alpha- synuclein plays a number of important roles in neurons in the brain, especially at synapses where brain cells communicate with each other. In DLB, alpha-synuclein forms into clumps inside neurons throughout the brain. This process may cause neurons to work less effectively and, eventually, to die.

The activities of brain chemicals important to brain function are also affected and the result of these two interactive degenerative processes is widespread damage to certain parts of the brain and a decline in abilities affected by those brain regions.

Lewy bodies affect a few different brain regions in DLB (please refer to previous blogs where brain function diagrams will alert you to the anatomy referred to below):

- The cerebral cortex, which controls many functions, including information processing, perception, thought and language

- The limbic cortex, which plays a major role in emotions and behaviour

- The hippocampus, which is essential to forming new memories

- The midbrain, including the substantia nigra, which is involved in movement

- Areas of the brain stem important in regulating sleep and maintaining alertness

- Brain regions important in recognizing smells (olfactory pathways)

What are the symptoms?

The most common symptoms include changes in cognition, movement, sleep, and behaviour.

Cognitive Symptoms

DLB causes changes in thinking abilities. These changes may include:

- Dementia – severe loss of thinking abilities that interferes with a person’s capacity to perform daily activities. Dementia is a primary symptom in DLB and usually includes trouble with visual and spatial abilities (judging distance and depth or misidentifying objects), multitasking, problem solving, and reasoning.

- Memory problems – may not be as evident at first as with DAT but often arise as DLB progresses. Other similar symptoms will be present and may include changes in mood and behaviour, poor judgment, loss of initiative, confusion about time and place, and difficulty with language and numbers.

- Cognitive fluctuations – unpredictable changes in concentration, attention, alertness and wakefulness from day to day, and sometimes throughout the day. A person living with DLB may stare into space for periods of time, seem drowsy and lethargic, and sleep for several hours during the day despite getting enough sleep the night before. His or her flow of ideas may be disorganized, unclear, or illogical at times.

- The person may seem better one day, then worse the next day. These cognitive fluctuations are common in DLB but are not always easy to identify.

- Hallucinations – seeing or hearing things that are not present. Visual hallucinations occur in up to 80 percent of people with DLB, often early on. They are typically realistic and detailed, such as images of children or animals. Auditory hallucinations are less common than visual ones but may also occur. Hallucinations that are not disruptive may not require treatment. However, if they are frightening or dangerous (for example, if the person attempts to fight a perceived intruder), then a doctor may prescribe medication.

Movement Symptoms

Some people living with DLB may not experience significant movement problems for several years. Others may have them early on. At first, signs of movement problems, such as a change in handwriting, may be very mild and thus overlooked. Parkinsonism is seen early on in Parkinson’s disease dementia but can also develop later on in dementia with Lewy bodies.

Specific symptoms of Parkinsonism may include:

- muscle rigidity or stiffness

- shuffling gait, slow movement, or frozen stance

- tremor or shaking, most commonly in the hands and usually at rest

- balance problems and falls

- stooped posture

- loss of coordination

- smaller handwriting than was usual for the person

- reduced facial expression

- difficulty swallowing or a weak voice

Sleep disorders

Sleep disorders are common in people living with DLB but are often undiagnosed. Recognising and treating sleep disorders can play an important role on in the treatment of DLB.

Sleep-related disorders seen in people with DLB may include:

- REM sleep behaviour disorder— a condition in which a person seems to act out dreams. It may include vivid dreaming, talking in one’s sleep, violent movements, or falling out of bed. REM sleep behaviour disorder appears in some people years before other DLB symptoms.

- Excessive daytime sleepiness—Sleeping 2 or more hours during the day despite sleeping through the night.

- Insomnia – Difficulty falling or staying asleep, or waking up too early.

- Restless leg syndrome — A condition in which a person, while resting, feels the urge to move his or her legs to stop unpleasant or unusual sensations.

Behavioural and mood symptoms

Changes in behaviour and mood are likely in DLB. These changes may include:

- Depression – a persistent feeling of sadness, inability to enjoy activities, and trouble with sleeping, eating, and other normal activities.

- Apathy – a lack of interest in normal daily activities or events, and less social interaction.

- Anxiety – intense apprehension, uncertainty, or fear about a future event or situation. A person may ask the same questions over and over or be angry or fearful when a loved one is not present.

- Agitation – restlessness, as seen by pacing, hand wringing, an inability to get settled, constant repeating of words or phrases, or irritability.

- Delusions – strongly held false beliefs or opinions not based on evidence. For example, a person may think his or her spouse is having an affair or that relatives long dead are still living. A delusion that may be seen in DLB is Capgras syndrome, in which the person believes a relative or friend has been replaced by an imposter.

- Paranoia – an extreme, irrational distrust of others, such as suspicion that people are taking or hiding things.

Other DLB symptoms

People living with DLB can also experience significant changes in the part of the nervous system that regulates automatic actions such as those of the heart, glands and muscles. The person may have:

- frequent changes in body temperature

- problems with blood pressure

- dizziness

- fainting

- frequent falls

- sensitivity to heat and cold

- sexual dysfunction

- urinary incontinence

- constipation

- a poor sense of smell

A person with DLB may also typically have some of the symptoms of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Although memory is often affected, it is typically less so than in Alzheimer’s disease.

As you will understand Lewy Body type dementia can be an extremely difficult form of dementia to live with, to care for and to live through as a family. It is extremely important to work with supporting professionals wherever DLB is suspected or diagnosed and a multidisciplinary plan of care must be formulated to provide a quality of life and a medical level of expertise whenever you encounter this form of dementia in your care home.

Just before we close on this week’s blog we must unusually end with an alert:

People with DLB may have severe reactions to or side effects from antipsychotic medications used to treat delusions, hallucinations, or agitation.

These side effects include increased confusion, worsened Parkinsonism, extreme sleepiness and low blood pressure that can result in fainting (orthostatic hypotension).

Some antipsychotics, including olanzapine (Zyprexa®) and risperidone (Risperdal®), should be avoided, if possible, because they are more likely than others to cause serious side effects.

In rare cases, a potentially deadly condition called neuroleptic malignant syndrome can occur. Symptoms of this condition include high fever, muscle rigidity and muscle tissue breakdown that can lead to kidney failure.

Antipsychotic medications increase the risk of death in elderly people with dementia, including those with DLB.

The person (where able) and family members, GPs and you, as paid carers and professionals, must weigh the risks of antipsychotic use against the risks of physical harm and distress that may occur as a result of untreated behavioral symptoms.

If antipsychotic medication is prescribed regular observation and recording must be undertaken and the risk must be displayed in the plan of care. If there are any sudden changes in condition, or any of the above symptoms appear and seem to be progressive, then these must be reported to the GP immediately.

Till next time.

Paul Smith – Dementia Care Expert